When further work required boatyard facilities, moving the hull to Yacht Haven in Stamford destroyed thousands of dollars worth of shrubbery and landscaping at the rented estate. This was not taken kindly. Months later the Fairfield County sheriff serving papers to seize the boat caused a premature sailing escape across state lines.

Minutes before the sheriff's anticipated nighttime raid, with a tugboat alongside while the crew finished the installation of the engine, the hull got underway on its own power from the middle of Long Island Sound for a short hop to Oyster Bay, New York. But we're getting ahead of ourselves.

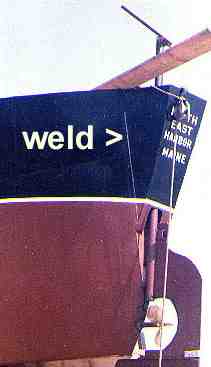

The months at Stamford's Yacht Haven were to plank and caulk the hull, partially plank the deck, and bend and weld 4 x 8 steel plates to make a rounded stern and a steel-sheathed bow.

A large block '56 Chevy V-8 converted to marine use was the auxiliary power.

A large block '56 Chevy V-8 converted to marine use was the auxiliary power.

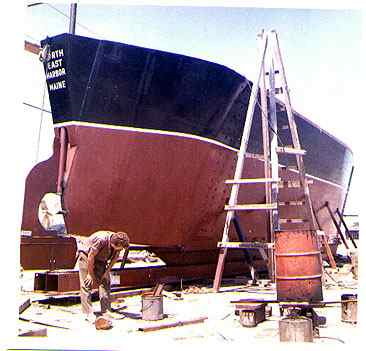

The work was done by Karl; his pregnant wife, Anne, whom the NY Daily News referred to as "Mellon's Honey Dew;" friends Andy and Chris Hyde who were the other married couple; Louis Clark, Anne's cousin from Long Island, and Danny Getchell, the teenage son of a Maine lobsterman. That's Danny in the photo above.

I met this crowd after spotting the 80' monster hull which dominated the Yacht Haven marina skyline.

Work was taking place on land alongside the parking lot near the Admiral Benbow Inn.

Work was taking place on land alongside the parking lot near the Admiral Benbow Inn.

After the basic construction and exterior painting in Stamford, the hull was to get temporary ballast and go under its own power to Northeast Harbor, Maine, for permanent ballast, bulkheads, cabins, wiring, plumbing, masts, and spars.

It was being painted black over red with a white waterline, and already the bow bore the name and the Connecticut registration CT 7940 F, when I started to hang out, taking photos and chatting.

As the time approached for temporary ballast, the sheriff came by to talk about the mess in Greenwich and Mellon knew time was short before padlocks would arrive.

As the time approached for temporary ballast, the sheriff came by to talk about the mess in Greenwich and Mellon knew time was short before padlocks would arrive.

Quickly the Travelift was brought over to launch the ship. The idea was to lower this unballasted, unstable, tippy hull a few feet into the water and fill the bilge with rocks as ballast, letting out Travelift cables as it settled until it could float upright on its own.

Truckloads of large ballast rock were unloaded near the launching slip. Load after load. It was 21-tons of large stones, still way short of the total ballast the Hilgendorf was designed for and required.

Launching at Yacht Haven proved it was a too-big ship in a too-small yard. Problem one was the lift cables. Too light for the job. Mellon bought heavier ones and had them installed. Then the slings were too short. Openings through the keel were cut so the slings wouldn't have to go under the I-beams. That worked. Slowly the Travelift raised the behemoth and gingerly (for a Travelift) moved it into position above the launch slip.

I had been filming all this in 16mm but ran out of film at this point. Too bad, because the drama began then. You can watch the one minute film on youtube.

As the cables began to play out and the hull descended, there was a sudden explosion. One of the Travelift cable motors sheared the four 5/8" bolts holding it to the frame and the motor was ripped off, left to dangle by its hydraulic cables.

The only reason she didn't capsize and sink right there in the launch slip was because the slip was 16' wide and the ship was 18' from keel to deck. The pilings held her up.

Here's how a Stamford Advocate reporter covered it.

After some penance to the Travelift gods and the installation of replacement bolts, the

Hilgendorf was righted and raised. Then the ballasting began. The small crew clearly needed more hands so I carried rock with the rest of them until the 21 tons was in the hold. The clock went all the way around at least twice. I think there was some pizza and Coke. When all the rock was finally in and the hull was floating and stable, we walked over to the Admiral Benbow for ales.

Mellon said "I'll have a Whitbred." I said, "Make that two." He said, "Yeah, I'll have two also" and a relationship was born.

Before the next round I was invited to be a member of this endless summer excursion and accepted. I had nothing better to do. Mellon was 26. I was 26. The rest were younger. They needed our mature guidance.

I went home to North Stamford for a shower and a kit bag and dad took me back to Yacht Haven so I wouldn't have to abandon my motorscooter there. Racing the sheriff, we got away under tugboat power in the middle of the night, had the engine aligned and welded to its bed within the hour, and powered off to Oyster Bay while water gushed in through gaps in the caulking with the pressure of a firehose.

The plan to put Karl's 1955 Plymouth station wagon on deck had to be abandoned. There was no time. As things turned out, hauling the Plymouth probably would have ended the adventure much earlier, and ended us as well.

We'll get to that.

Oyster Bay is less than 12 miles across Long Island Sound from Stamford and we were there a little after 2 am. Ask anyone in town because they heard us. A Chevy V-8 has two exhaust manifolds and ours led to 5" vertical black iron pipes sticking straight up a few feet above the hull. No mufflers.

On the open water we roared like a chorus of racing boats. In the bowl made by the hills ringing Oyster Bay we echoed like 76,000 trombones from hell. By the time we picked up someone's vacant mooring and shut the monster off, the houses in the hills above us blazed with light. In all likelihood those good people were praying, perhaps fearing Theodore Roosevelt was back from the dead to return to Sagamore Hill.

Water gushing in from the gaps in the cotton and oakum caulking made it clear we were going to sink before morning. We started the undersized Homelite bilge pump (eventually) but it was way too undersized for the job.

Half a mile across Oyster bay was one of the finer boatyards on Long Island, Jablonsky's. Boatyards have pumps. We fired up the roar from hell and made for Jablonsky's pier. Even in bed at 3 am miles away he probably knew when we got there.

As we tied up to his pier we noticed the HMS Bounty tied up on the other side. It was the latest replica of the famous ship. MGM built this one for the 1962 release of Mutiny on the Bounty with Marlon Brando as Fletcher Christian. Ted Turner later owned it and in 1993 donated it to the Tall Ship Bounty Foundation as a training ship. They in turn gave it to a private venture as a tourist attraction. It went to the bottom off the Carolina coast Oct. 29, 2012, a victim of hurricane Sandy.

Jablonsky came down mad as hell that we tied our sinking monster to his pier. We were so large that when we sank his pier would go down with us and maybe the Bounty as well. He had no choice but to lend us pumps. They did the trick.

The next morning we took turns diving 3 to 9 feet down with hands full of cotton and oakum batting, stuffing holes. When the danger was past and our Homelite could keep up, we bowed to Jablonsky and went back to the borrowed mooring. For two days we stuffed the rest of the holes until swelling finished the job and the leaks stopped for good.

The police motored over to visit us early on. Likely they intended to tell us to leave the private mooring but, seeing that our boat was three times the size of theirs and we looked dangerous, they accepted reality with polite understanding.

Meals and other needs of the crew made us something of a nuisance to the town of Oyster Bay. The kelly green tarp we slept under transferred its color to our hair, giving each of us the bizarre look associated with acid heads. No restaurant, not even the bars, allowed us in. The night we and our take-out porterhouse steaks were escorted off the roof of Karl's Plymouth and delivered back on board in a police boat was our last in Oyster Bay.

We checked the round bottom 275-gallon gas tank to make sure the ropes around the pipe clamp would keep it from flopping over, filled it at Jablonsky's by leading his gas hose into the bowels of the hull, and stuffed the rag back in the filler hole.

Respecting the characteristics of gasoline and its explosive vapors was not part of Karl's unique approach to things. Eventually this proved his undoing.

We started for Maine and got about 30 miles.

In the middle of Long Island Sound the Chevy V-8 started running rough, then quickly died. Someone checked the ignition points.

They were hopelessly burned. We put in a spare and set off again. A few hours later in Buzzard's Bay the Chevy died again. Burned points. We put in the last set and made for the Cape Cod Canal.

They were hopelessly burned. We put in a spare and set off again. A few hours later in Buzzard's Bay the Chevy died again. Burned points. We put in the last set and made for the Cape Cod Canal.

If your engine dies in that canal you have two choices: be swept by the eddies into the boulders that line the sides, and be destroyed, or anchor and be crushed by the next US Navy behemoth that takes 3 miles to stop.

We nearly made it.

At the northern edge of the canal, outside the entrance to the Coast Guard station, the points burned out again. By the skin of our behinds we eddied into the CG anchorage and tied up. As the engineer-designate it was my job to walk two miles down the highway to the first service station, buy all the points they had in our size, and ask why in hell they were burning out.

"Sounds like there's no ballast resistor," the man drawled. He was right. The Chevy was running a 12-volt battery and generator, but was wired for a 6-volt system. Points overheat at anything much above 8 volts so a dropping resistor is needed.

None of us thought of that.

None of us thought of that.

Install one resistor, new points, and until the Chevy later went under water, it was never less than perfect.

Before setting course for Northeast Harbor we needed to stop in Portland so the skipper could make some deals on gear for fitting out. Because of what follows you need a fuller picture of the Hilgendorf.

She was an 80' x 14' x 12' wood and steel hull with 5 feet of loose rock in the narrow bilge. Without the rock she would flop over like a drunken V. Even with the rock we were way under-ballasted. The calculated and painted waterline was several feet above where she was riding. To reach design stability she needed three times the ballast we carried.

Aside from rock there was little below deck but an open cavern. The engine was in the stern, and nearby the huge gas tank was lashed to a pipe clamp gripping one frame. There was a gas-powered bilge pump, a few hundred feet of 1" line, some personal possessions, car parts, a thunder jug, and left over construction lumber lying on the rocks. It was a bare bones hull needing everything to make it a ship.

The unfinished deck was partially planked with wide construction lumber, but uncovered. The seams were uncaulked, meaning there was a quarter inch gap between deck planks. For the first ten feet forward of the stern there was no deck at all, just an open abyss with the Chevy V-8 at the bottom. A captain's aft castle was to be built there. Temporary steering was by an 11-foot tiller coming off the stern post. The tillerman had only the last foot of decking to stand on. Behind him was the open abyss.

There were two flat-bottom rowboats circa 1930 sitting on deck like old, gray men awaiting death. They had served as rentals for decades before being tossed out as derelicts. One held a few thousand dollars worth of tools. The other, which had a deck of sorts, held our green tarp.

Ahead of the tiller was a gorgeous 19th century binnacle about 4' tall containing a first-class 12" compass served by a kerosene lamp. It was classy enough to have been a Mellon family heirloom. Forward was an immense Danforth anchor so heavy that if it ever saw use it would be lost forever whether it dug in or not. It was far too heavy for a small crew to raise without a windlass, which we didn't have.

There were two large openings in the deck ready to take the masts, one amidship and another forward covered by the anchor. The openings exposed two pairs of 4" x 8" deck beams side by side. The framing used in construction were 4x4s sistered tightly together with threaded rod to create immensely strong 4x8s. The planking was 2" thick.

She was so strong. She was so heavy. She was so strange. At the boatyard someone asked if it was to be an advertising sign. On the water people called it a "work boat."

On the way in to Portland Harbor we were treated to the sight of a loaded oil tanker that drew at least 20' heading straight for a passage no deeper than 4' at this tide. With but seconds to spare to change course for the channel, the helmsman was alerted and barely averted disaster.

An omen.

In Portland we linked up with a large Irish-American McSeaman with the most muscular hands I've ever seen. Jim McGowan could, and did, braid wire rope into short splices, long splices, and eye splices with the ease normal seamen handle hemp. We watched him do it. A good man to drink with but stay on his good side. His knuckle sandwich would be any man's last meal.

We enjoyed his company, his whiskey, and his waterfront cottage a day too long. The morning we set out for the final leg to Northeast Harbor a heavy swell had come in from the Atlantic. Waves trough-to-top were 12 feet. We headed straight into them to clear the rocks north of the Portland entrance.

Everyone had a thrill laying over the bow watching the steel sheathing knife up and down. It was a small shock to see up close that the unfinished sheathing left a 6-ft gap from the bow to within a few inches of the design waterline.

Thanks to the light ballast we rode two feet below that line. Whatever was sealing the unsheathed bow was effective. We took no water there.

Thanks to the light ballast we rode two feet below that line. Whatever was sealing the unsheathed bow was effective. We took no water there.

I was the tillerman. About 4 miles into the Atlantic the gentle swells moved closer together, the troughs deepened, and we were now powering into 16-foot waves.

Suddenly the Hilgendorf pitched down so abruptly that the magnificent antique binnacle went off-balance and fell forward. Seems it hadn't been fastened to the deck. I gripped the 11' tiller and wrapped my legs around the binnacle before it fell, hauling it back upright. A whoop and holler brought crewmen running with hammers and lag bolts. The binnacle, at least, was to stay with us.

Karl came over and said we were safely off shore and should head north. I don't know what he was feeling, but my instincts rebelled at the thought of swinging 90 degrees and taking those 16-foot waves broadside in a narrow, under-ballasted hull with huge gaps in the deck for water to pour through.

But it was that or Portugal, so I swung the turn and ohmygod all hell broke loose.

The first wave we took abeam pitched us so steeply that the derelict rowboat holding the tools slid over the side, filled with water, and went straight to the bottom. Oh well, Mellons can replace tools.

Two crewmen grabbed the second boat before it could follow. A third put a line to the cleat on the rowboat's deck and looped the other end over the tiller, throwing it back so the loop fell over the sternpost. All on its own the next wave launched the lifeboat. It was empty, the green tarp having been stowed below deck.

The hawser stretched out as it should, not fouling the prop or rudder, and now we were towing our only lifeboat. For no more than ten minutes. Then its plywood deck ripped off and the rest of the old gray tub slid beneath the water. For much of the day until the plywood deteriorated we towed that deck. After that we towed the cleat,

probably a 12"like this one.

The sea was running stronger. It wasn't until the 12th or so wave that the massive Danforth anchor began to slide. It didn't move but a few feet so another line was procured to secure it to the exposed deck beams.

The Hilgendorf rudder was badly balanced.

A note had been made to fix that and weld on a larger leading edge. When underway at 3 to 4 knot cruising speed it took 40 lbs pressure on the 11-foot tiller to deflect the rudder. That was one-fourth my weight, but having recently carried my weight in ballast every 15 minutes for 24 hours, the tiller was no problem.

A note had been made to fix that and weld on a larger leading edge. When underway at 3 to 4 knot cruising speed it took 40 lbs pressure on the 11-foot tiller to deflect the rudder. That was one-fourth my weight, but having recently carried my weight in ballast every 15 minutes for 24 hours, the tiller was no problem.

That's a good thing because for the next 12 hours until 10 PM I remained the tillerman. Everyone else had a more important job - keeping the Hilgendorf from being battered apart by loose rock flying from side to side, plank to plank, several feet below the waterline.

There were seven of us aboard. When the flying rock was discovered, the other six moved below. They stood the left over construction lumber on edge lengthwise down the middle of the bilge. Three of them sat on each side, pressing their backs to the hull and their feet to the planking, holding it upright. Now the rock could only fly two feet between this barricade and planking. It worked. The planks held fast.

Up above I watched the pitching increase. We began to dip the rails and started taking on water through the uncaulked deck. It became necessary to minimize the pitching. I longed to cut the Danforth loose and get the weight off the deck but that wasn't my option.

It flashed through my mind that if we hadn't been chased out of Yacht Haven by the Honorable Paddy Marouk, sheriff of Fairfield County, Connecticut, Karl's Plymouth station wagon would have been lashed to the deck. Had we been carrying that 3,408 lbs on deck, the first wave abeam would have careened us and we'd have kept right on turning over, spilling the ballast across the planks. On her side she'd have filled with water at the speed of a bailing bucket and gone down even faster than the lifeboat.

We were spared that and had a chance to make it so long as the deck didn't go under. That was a matter of making constant broad swings of the rudder as each wave and trough passed to avoid waves coming directly abeam, even if by just a few precious degrees. We crab-walked that way for eight hours until the seas dropped and the rails no longer dipped.

Only two things interrupted that 12-hour watch.

When the seas were at their worst I became aware of a "thwump!" followed by a "sprang!" with every wave. I looked back at the curved, welded hull forming the stern and saw that a 4 x 8 steel plate was flexing in to hit a vertical steel rail, "thwump!" and springing out with a resounding "sprang!"

A few inches away from this movement was a vertical weld line 8 feet long.

How many flexes does it take to crack a weld? Less interested in research than survival I let go the tiller and jumped down to the rail behind the Chevy, pulled off a Vise-Grip kept there for convenience, and at the next "sprang!" jammed the plier into the gap. It was a tight fit. It never moved. It's probably still there.

How many flexes does it take to crack a weld? Less interested in research than survival I let go the tiller and jumped down to the rail behind the Chevy, pulled off a Vise-Grip kept there for convenience, and at the next "sprang!" jammed the plier into the gap. It was a tight fit. It never moved. It's probably still there.

Night fell and unfamiliar navigation aids lit up along the coast but the compass did not. The binnacle used a kerosene lamp and we had no kerosene. I hollered for light and up came a headlight and a parking light stripped from a car weeks ago just for this trip. Wire cascaded down to the Chevy battery for power, a few coils resting on the hot engine. The compass was useful once again. But where in hell were we headed?

Karl and Andy came up with a chart. Even in the dark they looked like hell. Constant rocking in the bilge for 9 hours kills anyone's equilibrium. They could barely stand from being cramped so long between barricade and hull. I refused to think about the cramped womb down below a third of the way through its job producing the future Matthew Mellon.

The chart showed we had made little progress up the Maine coast and weren't likely to make Northeast Harbor without rest and possibly gas. What was slowing us would continue to. The seas still ran high, the 60-foot keel beams had 2 huge cavities creating substantial drag, and we were towing the damn cleat. The decision was made to make for the nearest good harbor.

That was Boothbay Harbor 6 hours away.

We plotted the course, memorized the lights, and droned on, the blast from the Chevy's twin pipes having become a song of salvation, though decades later my hearing paid the price. At 10 Karl relieved me at the tiller and I replaced him at the barricade. Once jammed in place I slept.

Four hours later at 2 am his call for light woke us. The water was calm. We were at Boothbay Harbor. The headlight found a mooring with a dingy tied to it and we made fast. The others were for rowing ashore and finding a motel but I stayed behind, remembering that a practically dry sleeping bag was stashed under the tarp.

At 9 in the morning Andy came to get me. It seems the motels had been closed and the crew spent the night sleeping on the floor of an all-night laundromat. We took rooms, bathed, and slept an entire 24 hours. Then ate for two more. A car arrived to carry off the working womb, and we completed the cruise uneventfully to Northeast Harbor.

That was the honeymoon voyage of the Hilgendorf.

The rest of the marriage didn't go that smoothly, what with ramming a barge storing lobster traps, capsizing inch-by-inch on the outgoing tide and flooding the hull as it came in because we ignored tide tables, and in the end exploding and being destroyed by fire.

Instead we remember the good times.

* good times at Dilly Cottage where we were awakened morning after morning by the Carmina Burana at ear-splitting volume, and only the last person to breakfast could turn it off;

* good times at in-law JPJ Baltzell's Pink House;

* losing the Matinicus Rock Race by more than 8 hours in Baltzell's boat, and nearly destroying the Northeast Harbor town pier at 2 AM;

* more problems in the Cape Cod canal transporting that racing boat to City Island;

* riding out a hurricane in Port Jefferson while more than a dozen US Navy seamen drowned trying to get back to their ship;

* delivering a carload of contraband across New England after temporary Brazilian shipmate Carlos DaSilva and I stripped and abandoned his Chevy in Westport;

* partying with legendary Lady Astor at the Pink House; and

* having a 3-lb lobster - even two apiece if we were hungry - several nights a week just by saying yes to Danny's lobsterman father on his daily visit.

Will we ever tell the rest of the story? Probably not. Twenty years later on March 31, 1983, at age 46, Karl killed himself on Mt. Desert Island. He had remarried and left one daughter and three sons. Later in 2018 at age 54, his first son Matthew also took his own life.

The press attributed the deaths to bi-polar disorder.

What happened to the Hilgendorf?

During construction, I planned to install the gas tank according to Coast Guard regulations, with a filler pipe on deck. Karl refused that, fearing water leakage, and insisted the tank be filled in place, in the bilge. That was both illegal and dangerous. In his absence one day I did it the right way. When he saw it, he fired me from the crew and had my filler pipe removed.

Construction continued and in November she was ready for a trip to City Island, NY, and installation of the electrical system, which would have been my job. At Portland the crew stopped for gas. The gas boat came alongside, the hose was led below deck, and when the nozzle touched the tank there was a spark, an explosion, and a fire that burned her to the waterline. There were injuries but no one was killed.

Finito.

It made a tiny story in NYC papers the same day JFK was assassinated.

In 2008 while cleaning out a filing cabinet I ran across this 1963 Stamford Advocate report. The reporter got more things right than wrong.

Then in 2011 the former Christie Hyde sent copies of two key items:

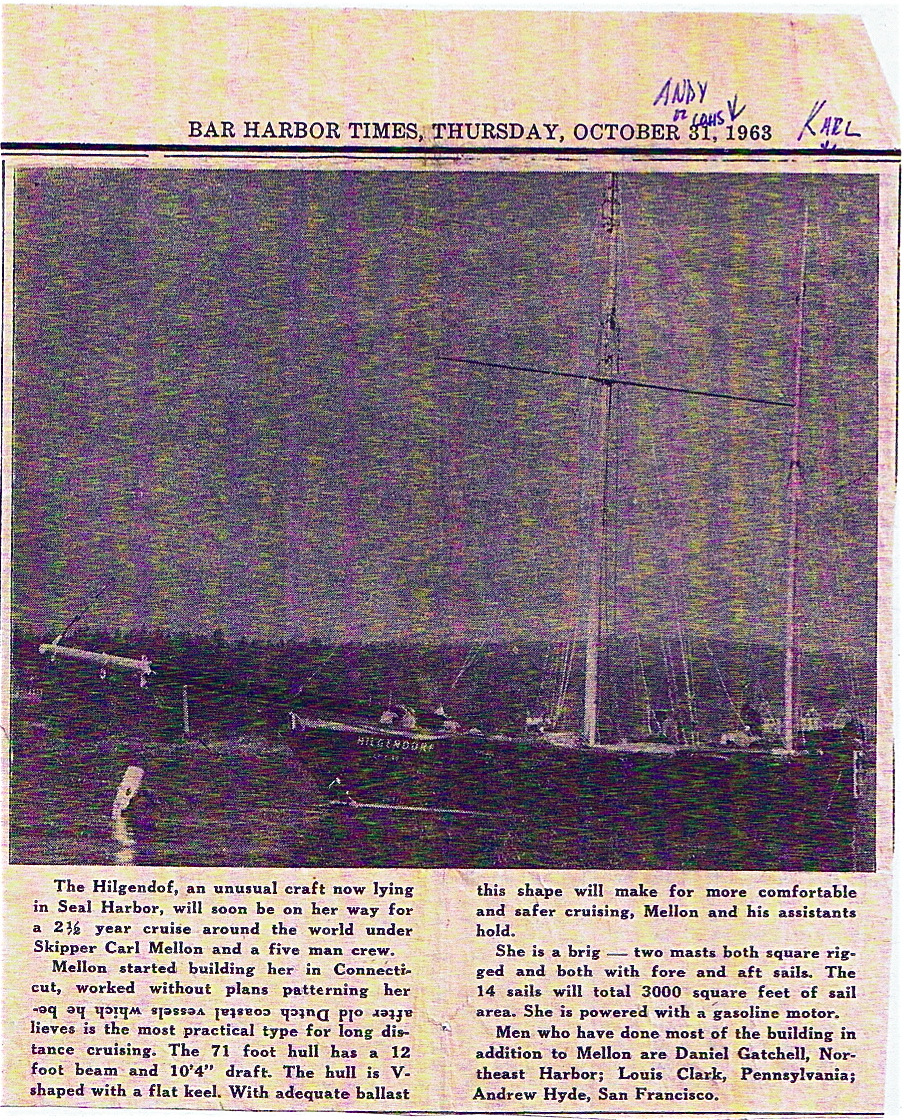

An Oct. 31, 1963, newspaper photo of the Hilgendorf in Seal Harbor. She is fitted with fore and aft masts, a topmast on the foremast, spars, and her bowsprit. She appears to be fully rigged with standing and running rigging.

The line typeset upside down & backwards says

"after old Dutch coastal vessels which he be-"

And the last piece in Hilgendorf history, from the front page of the Nov. 22 Greenwich Times, sharing space with the JFK assassination story:

Raybo, that's me,

in later years preparing for a James River bateau race.

The author lives in Virginia where for many years he owned the 45' Chesapeake Bay bugeye ketch Applejack.

Subsequent owner Lew Allen and Seaford builder Carl Peterson turned her into a familiar and important Hampton Roads ketch Chesapeake.

After another sale she is currently berthed in Havre de Gras.

=======================

There's no question he would have been given command of the largest sailing ship of all time, the 5-masted

, since he conceived it, but he retired shortly before it was launched Oct. 30, 1903. Preussen was struck and shoaled a few years after launch.

In the last years of the 20th century, her hull was found in Gdansk, Poland, and sold to an adventurous Swede not unlike Mellon. At a cost of $60 million he extended the hull and created the "Royal Clipper," at 5,000 tons the largest sailing ship of all time, larger than Preussen. It sails the trade winds giving paying passengers the same luxuries they get on normal luxury cruise ships.

Note that all of Capt. Hilgendorf's commands began with the letter P. All the ships of the Laeisz Line did. Years later in 1925 the Potosi cargo caught fire and the crew had to abandon ship. The drifting hull was later sunk by an Argentinean cruiser aptly named Patria.

"Partisans of the American clippers may be surprised to find that the Germans produced not only the greatest ships but some of the greatest captains as well. To Villiers, once a skipper in sail himself and not easily given to hero worship, the giant of them all was Robert Hilgendorf, the "Devil of Hamburg."

"No one ever equaled his skill at rounding the Horn, and there were plenty of sailing men who believed he could control the winds with black magic. Hilgendorf himself did not care to press his skill; he quit at an early 50 to take a soft job ashore with an insurance company."

Hilgendorf also designed a sextant for use in low light after the sun went down. You can read the details of one for sale here.